The past years we have seen a rise of transmedia storytelling. Increasingly companies tell their stories across different installments, such as films, television series and games. The rich universes of Star Wars, The Wizarding World and Marvel are continuously added to with new content to engage global audiences.

Legacy sequels, large franchises, theme parks – transmedia is booming. Some examples from this year include the anime The Lord of The Rings: The War of the Rohirrim, the television series The Penguin, and the vast add-ons to Nintendo World in Universal Studios. Transmedia has been analyzed often as a productive tool. Audiences are stimulated to participate in this format, and it’s seen as a success factor in building fan communities.

However, today transmedia is almost the default and the result is not always great. Even the most passionate fans often lament the endless iterations of the same stories, the lack of originality in the media landscape and the self-referential nature of these formats. To the most cynical consumers, transmedia is just another corporate scheme by now.

It’s high time to discuss some of the challenges of this format. What are some of the things that we need to be mindful to when designing a good transmedia story or world?

Narrative Cohesion

Transmedia stands or falls with good coordination of the format. Building a large story world across platforms is a daunting task, and it often requires the coordination of different teams. These are complex narrative structures, dispersed across media. In the best cases this leads to exploration of the canon, further knowledge and filling in the gaps. In the worst cases, it seems like creators are making the pieces fit.

The referential nature of transmedia storytelling can be beautiful for fans, since it confirms their knowledge of a franchise. Since these products are not stand-alone, viewers need a lot of knowledge at their disposal about the lore and its characters. In the best case, transmedia is a scavenge-hunt for audiences, who are asked to think along. As transmedia theorist Henry Jenkins writes: ‘Consumers become hunters and gatherers moving back across the various narratives trying to stitch together a coherent picture from the dispersed information.’

However, the encyclopedic nature of this format can also confuse audiences or lead to jarring writing. Obscure references from the canon are updated and made to seem meaningful in hindsight. A small but poignant example is the back story of Hodor in Game of Thrones, connected to a comedically tragic scene with the infamous line: “Hold the door.” The attempt to expand the character’s backstory fell flat here because no one was curious about the origins of Hodor’s name—let alone eager for this overly dramatic explanation.

The best transmedia stories provide cohesion and depth of character. This works best in stories that are quite independent, such as Loki or Agatha All Along. Areboot or renewal can also be a great platform for character work. DC has done some stellar work in this space, for instance in Batman: Caped Crusader, which rewrites the backstories of iconic heroes and villains in interesting ways.

Quantity over Quality

Transmedia can also quickly lead to too much content, making it hard for fans to keep the overview. Who can still keep track of almost twenty years of content within the MCU, currently containing 34 films and many spin-off series across different channels? Large companies, such as Disney, have to continuously churn out new content to enhance their brand and streaming services. This shows in the quality of the products.

In other words, transmedia can foster a culture of quantity over quality. It can also lead to a culture of exclusivity since it’s not accessible for viewers that are less familiar with all products. This leads to estrangement for some audiences, while even the invested ones might experience a feeling of transmedia fatigue.

Most successful are the products which focus on depth. That strive for “more from” rather than “more of” a narrative world. Again, this is where a show like The Penguin shines, by providing us a detailed character study of a villain. Another best practice is to expand the potential market by creating standalone products for different audience segments. The different LEGO games and animation series are a good example of this, which are highly enjoyable by themselves and don’t require too much prior knowledge from their audiences. The same goes for the fantastic documentary Piece by Piece, told completely in LEGO as a brickfilm.

The Business of Transmedia

Another restraint is caused by the franchising itself. Franchises now span decades, which Wired dubs a “franchise frenzy”. In 2007, Henry Jenkins already wrote that transmedia is deeply connected to business:

‘The current configuration of the entertainment industry makes transmedia expansion an economic imperative, yet the most gifted transmedia artists also surf these marketplace pressures to create a more expansive and immersive story than would have been possible otherwise.’

Franchising is now the norm and creators go through great lengths to create these. A great example is the rise of legacy sequels. These sequels are set decades further in the time line, allowing for the presence of aging characters and stars. Ghostbusters, Jurassic Park and Beverly Hills Cops each have new sequels, hailed with varying degrees of success. Nostalgia is not enough to drive a story or franchise. Moreover, these sequels often drown out other initiatives in the media industries, leading to a very homogeneous landscape of revival blockbusters and long lasting franchises.

Transmedia can of course also be sparked by fans themselves. Transmedia formats encourage participation by fans, knowledge-seeking and even creativity. Fan fiction, AMV’s, cosplay and other fan content can be understood as a form of transmedia. These fan works are also capitalized on by the industry and by big tech platforms. An apt term for this is “user-generated profit”, as James Muldoon conceptualizes in his book Platform Socialism. The content of consumers – based on their creativity, their critical thought and their daily lives – is commodified for profit in today’s platform economy. Instagram, Facebook, Twitch and other platforms capitalize on fan engagement while their users do all the hard work.

In other words, transmedia also can be challenged from an economic and political point of view. It leads to participation and content that is raw material for companies, who might also sell this for advertising purposes or exploit it for other practices, such as the training of generative AI.

Transmedia cannot be truly set apart from corporate interests. However, Japanese pop-culture can be inspiring since that’s where the “media mix” is a default in the media industry. Because rewriting and retelling is very common in that production culture, franchises can go in interesting directions. Think of the rewrite of Evangelion, which provides additional narrative closure for Shinji, Gendou and other characters. Through an alternative time line, the characters can finally confront each other, heal, and engaging in new relationships.

What’s Next?

Overall, transmedia is now in a surge in the West. We are still in a phase of experimentation, and trying to understand which stories are worth telling, and which should be left to the imagination of the audience.

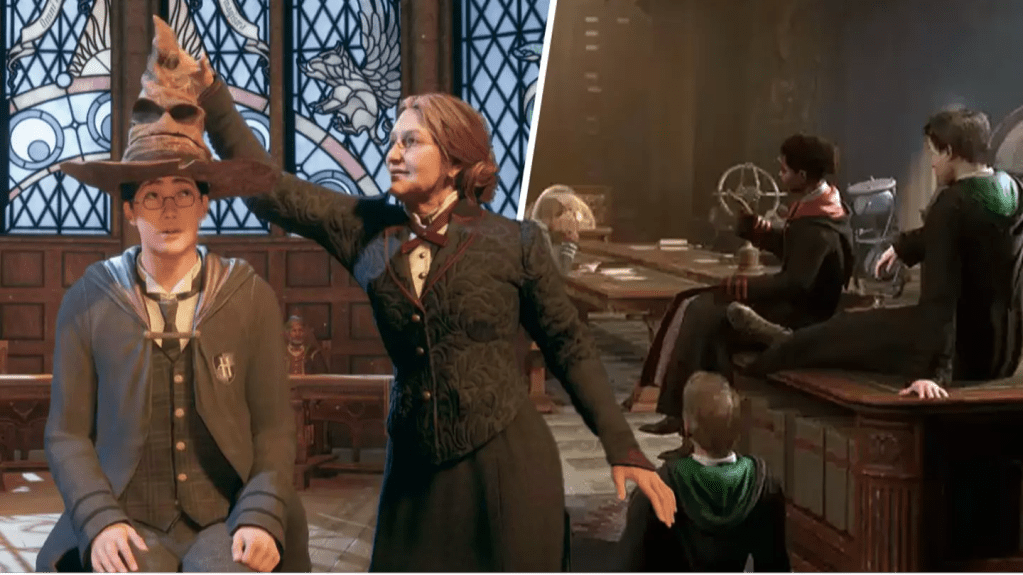

I look forward to new initiatives a lot, but I’m also weary. Tying Hogwarts Legacy directly the new Harry Potter series? I’m hesitant. Toy Story 5, Wicked? I need to see it to believe it. Still, I think there’s much potential still left in connecting games, merchandise and material fan culture more to canon products and storytelling. I’m curious to see where these trends go, so stay tuned.